- Published on

- ·29 min read

Agent Autonomy - Part 2: Going Beyond Algorithms

- Authors

- Name

- هاني الشاطر

Introduction

In Part 1, Agent Autonomy - How to solve algorithmic problems, we explored the realm of agent autonomy specifically applied to solving algorithmic problems. We traced the historical arc—from classic algorithms to meta-heuristics to ML-based solutions to neuro-symbolic methods. We saw that for specific settings, coding agents can be as powerful as human engineers.

The key insight? Agent autonomy works when you have:

- Complex but bounded problems: Small to mid-scale problems with clear constraints and verifiable success metrics.

- Immutable harness: The critical, unchangeable evaluator that defines the problem and prevents "cheating".

- Code evolution (AlphaEvolve style): Using coding agents to iteratively mutate and recombine code solutions and innovate new strategies.

- Zero code implementation: Leveraging the agent's ability to use simple tools (like Bash) rather than building complex orchestration frameworks.

- How to design your own: Tips to build your own coding agents to solve algorithmic problems with tools like Claude Code.

If you look back, this is an amazing shift. We had zero code, but still we achieved a state-of-the-art circle packing solution that beats DeepMind's AlphaEvolve paper. Even though we did not extensivly try other kind of problems, it is still a remarkable result in my humble opinion.

Beyond Algorithms: What Does a Vibe Coder Actually Need to Solve?

Solving complex bounded problems and beating the complexity beast is very promising. But let's be honest—in real-world applications, you rarely face problems with clean immutable harnesses.

Let's raise our ceiling and ask a more practical questions. To draw the picture we need an example, and the example I will be using here is an educational demo for Merge Sort and Count-Min Sketch. Educatonal demos are bounded but have deep human interaction and complexity that make it a good testbed for agent autonomy. Imagine that you can build a demo that is as beautiful and powerful as distill.pub articles or Jay Alammar's Demos.

To establish a baseline, here are demos built by a coding agent without agent autonomy:

Merge Sort Visualizer

A Divide and Conquer sorting demonstration.

❓ Recursion

Merge sort uses a top-down recursive approach. It divides the array into single elements before merging them back in order.

❓ Stability

Merge sort is stable, meaning elements with equal values maintain their relative order, which is crucial for multi-key sorting.

❓ Complexity

Time:O(n log n)

Space:O(n)

As you can see, the demos are functional but not particularly engaging. They miss the visual concepts that make them truly educational and show a limited understanding of what humans find compelling.

What Does It Mean to Vibe Code Something?

Let's look under the covers. When you vibe code a bounded creative problem, you're actually operating on five distinct layers:

Layer 0: The LLM

How do you make a smart machine? This is the foundation—the raw intelligence that powers everything. Billions of parameters, trained on the written record of humanity. Transformers, attention, pre and post training. This layer of abstraction that is largly provided by frontier labs (OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta). Most likely, you don't build this—you use it.

Layer 1: The Coding Agent

How do you turn an LLM into an effective coding partner? Raw LLMs can write code, but coding agents add crucial infrastructure: efficient diff tools for precise edits, planning and search for complex tasks, execution APIs to run and test code, context management (compression, retrieval, prioritization) when your session is too long for an LLM, also code repo understanding or mapping. This is Claude Code, Antigravity, Cursor, Aider, Devin—the tools that make LLMs practical for software development.

Layer 2: Software Infrastructure

Then, your AI can code, but still software engineering is a nightmare, auth do not work, infra is difficult to setup, where to host your database, how to build efficive envirments for test, prod, which stack to use? or in one sentence, how to manger the full software engeinering cycle. Vibe coding platforms like Replit, Lovable, Github Spark help you here—they provide tested stacks that work with AI coding, simplified tooling for databases, hosting, auth, and procedural recipes that make common patterns easy. This works well for simple applications. For larger systems, you still need software engineers to design and scale more nuanced architectures, but in any case, this is the software infra layer.

Layer 3: The Core Problem-Solving

How do you actually solve the creative problem? This is uncharted territory. Current vibe coding platforms totally depend on you to drive and solve these problems. They provide basic support through planning prompts and compute (like Chrome testing), but the intellectual heavy lifting is human. For bounded problems—our focus in this post—this is where the real challenge lives.

Layer 4: Intention & Goals

What are you actually trying to achieve? This is how we evolve our goals and opinions as we build. Software development is often agile, driven by OKRs that refine over time. Same here: you start simple ("visualize merge sort"), see what you built, and refine what you actually need ("help learners build intuition for divide-and-conquer thinking"). The goal emerges from the work.

Here's how this plays out in practice: say you want to build a demo for Merge Sort. Should you train an LLM to build demos (Layer 0)? Build infrastructure for educational demos (Layer 2)? Or just vibe code it (Layer 3)? Working on the right layer of abstraction saves you tons of overhead and lets you focus on what actually matters. For most vibe coders, the answer is Layer 3—the problem-solving layer. That's where the leverage is.

Layer 3 is not automated. At all. Vibe coding platforms hand you the tools and say "you figure it out." What if agents had a deep mode—autonomy on Layer 3? In Part 1 we put algorithmic discovery on autopilot. Could we do the same for practical applications?

In the Vibe Coder's Seat (Layer 3)

Layer 3 is what I consider the fun part of vibe coding: solving problems where success is subjective, feedback is noisy, and the search space is creative. No deterministic harness function. No gradient to follow. Just "make it better." For our Merge Sort demo, correctness isn't whether the algorithm runs (that's trivial)—it's whether a learner walks away understanding divide-and-conquer. The agent must reason about what humans find confusing, design visualizations that reveal insight, and iterate until something clicks. What intellectual challenges does this demand? Through research and experimentation, here we set in the vibe coder's seat and identify six—not implementation problems, but the fundamental difficulties that make vibe coding hard.

Let's map each to our running example:

1. Handling Computational Complexity

The Problem: Building a demo involves a combinatorial explosion of decisions. Layout: tree view or flat? Colors: by state or by operation? Interactions: step-by-step or continuous animation? Each choice branches into more choices. For a Merge Sort demo alone, you face thousands of possible design combinations—and that's before considering pedagogical framing.

Most interesting problems are NP-hard. You can't enumerate all options. Traditional solutions—heuristics, approximation algorithms, meta-heuristics—help, but they require you to be the expert who invents the right approach.

What We Know: In Part 1, we moved from algorithms to the algorithm vortex. We flipped the script: instead of you designing an algorithm that searches the solution space, let a coding agent search the algorithm space itself. This is neuro-symbolic: a neural coding agent producing symbolic code.

For Demos: Same principle. Don't search for "the best demo." Search for the best approach to building demos. Let the agent invent visualization strategies, pedagogical structures, interaction patterns. The complexity explosion isn't in finding answers—it's in finding the right questions. Let the coding agent explore solutions for you.

2. Decision-Making Under Uncertainty

The Problem: Creative problems have subjective, uncertain feedback. "Is this demo good?" might get different answers on different days. No loss function, nor a fixed harness function. So how do you optimize?

The RL Primer

Unlike supervised ML where you get (input, label) pairs, reinforcement learning is about figuring things out yourself. You take actions, get rewards, and learn what works. The beauty: we don't need to know how a robot should walk—just how to tell it "you're doing great." It explores and figures out walking on its own. Like telling a kid: get chocolate? Great. Grounded till tomorrow? Not great.

The RL loop:

- Take an action in the environment

- Observe the reward (positive or negative feedback)

- Update your policy to maximize future rewards

- Repeat until you learn optimal behavior

But RL has two problems:

- You need a reward function. Someone must define "good" mathematically. For "make this demo engaging"? That's subjective.

- Random exploration is expensive. A robot takes forever to even stand up by random flailing.

World Models Flip the Script

In the late 2010s, researchers asked: what if we skip the expensive exploration? If a model understands the environment and can imagine future trajectories, it can learn from dreams—simulate actions without crashing real cars. World models revolutionized RL. Robots could learn way faster.

Around the same time, transformers were revolutionizing NLP. RL researchers noticed something interesting: transformers trained on text have already seen countless human trajectories—problems to solutions, confusion to clarity. They're world models by default. And they can predict future sequences—that's just what language modeling is.

What if we flip RL upside down? Instead of "random actions → discover rewards," start with the desired outcome and predict actions that lead there. Train on videos of people walking 1m, 10m, 100m. Now ask: what does walking 1000m look like? The model extrapolates. Decision Transformers (2021) made this concrete: train on trajectories with their returns, then at inference specify the return you want. The model generates actions to achieve it. Competitive with state-of-the-art RL—no value functions, no policy gradients. Just sequence modeling.

LLMs: Upside-Down RL Without Knowing the Reward

Here's the key insight that makes LLMs different: upside-down RL still needs you to specify the reward. Decision Transformers need numerical returns. But what if you don't know the reward? "Make this demo more engaging" isn't a number.

LLMs solve this. They've absorbed so many human trajectories—codebases from idea to implementation, tutorials from confusion to clarity, designs from problem to solution—that they can implicitly detect what "engaging" means from context. You don't specify a reward. You describe it. Or give examples. The LLM infers the implicit reward function and generates a plausible path.

Prompt with "make this more pedagogical" → the LLM infers the goal and produces: add step-by-step explanations, use visual metaphors, include practice questions. No one defined "pedagogical" mathematically. The model extracted it from patterns in human teaching.

This is upside-down RL at massive scale—trained on the entire written record of human problem-solving, with implicit reward detection from natural language.

OPRO: Making It Explicit

Google DeepMind's OPRO (Optimization by PROmpting) systematizes this loop:

- Show the LLM past solutions and their scores

- Ask: "generate something better"

- Evaluate, add to history, repeat

Example: Given data points for linear regression, OPRO doesn't compute gradients. It sees coefficient guesses and their errors, proposes new coefficients, and converges to optimal solutions—pure language-based optimization.

Results on prompts:

- Up to 8% improvement on GSM8K (grade-school math)

- Up to 50% improvement on Big-Bench Hard (complex reasoning)

- Discovered prompts like "Take a deep breath and work on this problem step-by-step"

LLMs can optimize anything—code, designs, strategies—given natural language objectives.

Here's an example from the paper—OPRO solving the Traveling Salesman Problem. The meta-prompt shows past traces and their lengths. The LLM generates a new trace with shorter length, purely by reasoning about the pattern:

Vibe Coding = Upside-Down RL on Steroids

Vibe coding is OPRO generalized:

- "Make a merge sort demo" → initial attempt

- "Needs to be more pedagogical" → refined

- "Add step-by-step controls" → refined

- "Colors should track recursion depth" → refined

Each prompt refines the reward description. The LLM infers "better" and explores.

The takeaway: When you vibe code, the AI agent is doing upside-down RL with an implicit reward—inferred from your instructions, previous attempts, and your corrections. No math. Just language.

3. Theory of Mind

The Problem: Applications we build don't just need to function—they need to understand users. Educational content must model what learners will understand, misunderstand, find engaging, or find confusing. This requires reasoning about other minds—what cognitive scientists call Theory of Mind (ToM).

Here's the challenge: when you design a Merge Sort demo, you need to predict that a learner will get confused about why we divide before we merge. You need to know they'll miss the recursive structure if you only show bars moving. You need to anticipate the question: "but why not just sort directly?"

This is hard. Most engineers design for themselves—people who already understand. Designing for the confused requires modeling a mind that doesn't know what you know.

What We Know: LLMs have emergent Theory of Mind—and the research is striking.

A 2024 study in Nature Human Behaviour (Strachan et al.) compared GPT-4 with human participants across ToM tasks:

- False belief tasks: GPT-4 solved 75% of novel false-belief scenarios—matching 6-year-old children (Kosinski, PNAS 2024)

- Intention inference: Matched or exceeded human performance

- Indirect requests: "It's cold in here" → correctly inferred "close the window"

- Recursive beliefs: "I think you believe that she knows..." (up to 6th order)

"GPT-4 matched or exceeded human performance on false belief tasks, indirect requests, and misdirection." — Strachan et al., Nature Human Behaviour 2024

The model didn't "learn ToM" explicitly. It emerged from training on human communication—where understanding other minds is essential.

For Demos: We prompted Claude to evaluate a Merge Sort demo as a confused student. Its response: "I don't understand why we keep dividing. It feels like we're making the problem more complicated, not simpler. Where's the payoff?" Exactly what a real novice would say—and it guided the demo evolution toward showing the "merge payoff" more clearly.

4. Creative Horizons (The Honest Gap)

The Problem: Creativity isn't just exploring a search space—it's inventing new dimensions to explore.

RL can exhaustively search known state spaces. AlphaGo explored Go positions better than any human. But it never asked: "What if we changed the rules of Go?" Creativity requires reframing the search itself.

For demos, this means: a skilled human designer might look at Merge Sort and say, "What if we visualized it as a family tree instead of bars? What if we told its story as a narrative, not an algorithm?" These aren't moves in a known space. They're expansions of the space itself.

What We Know: This remains the honest gap.

- RL has hit limits: Exploration in structured spaces works. Long-horizon creative leaps—inventing new genres, reframing problems—remain mostly human

- Horizons are growing: METR's research (Kwa & West et al., 2025) shows AI task-completion horizons doubling every ~7 months since 2019. Claude 3.7 Sonnet can complete tasks requiring ~50 minutes of human work. But we're still far from matching human creative leaps that take days or weeks of background thinking

- Planning helps creativity: Expanded planning horizons correlate with creative insights in humans. LLMs can plan, but they don't naturally do open-ended exploration

"The 50% task completion time horizon—the duration of tasks an AI can complete autonomously with 50% probability—has been doubling approximately every seven months." — METR, 2025

The twist: We can't solve this gap with better models. But we can constrain it.

For Demos: This is where skill-based prompting matters. Skills encode human creative heuristics:

- "Try a tree visualization instead of bars"

- "Use color to track state through time"

- "Show before/after comparisons"

- "Add a 'why does this matter' framing"

Skills don't make the LLM creative. They guide exploration into productive regions that the LLM wouldn't discover on its own. We trade infinite creativity for guided creativity—and for bounded problems, that's often enough.

5. Evaluation (The Hardest Problem)

The Problem: How do you score a demo? This is where most AI projects quietly fail. Without a mathematical loss function, you need human-like judgment—but human judgment doesn't scale. And the obvious solution—rubrics—creates its own disaster.

Why Rubrics Fail: Reward Shaping Gone Wrong

Rubrics seem like the answer. Define criteria: "Is the UI clean?" "Does it explain the concept?" "Are the colors consistent?" Score 1-5. Sum up. Done.

This is reward shaping—and it's a classic RL trap. Goodhart's Law: "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

The CoastRunners Example

OpenAI trained an RL agent to play CoastRunners, a boat racing game. The reward: maximize score. The agent discovered that hitting turbo boosts on a small loop gave more points than finishing the race. Result: the boat endlessly circles a tiny section, on fire, crashing into walls—but racking up a high score. The shaped reward (points) completely diverged from the intended goal (winning races).

The Coffee Example (from Stuart Russell's Human Compatible)

You ask an AI to make coffee. Simple enough. But the AI has learned something: if it gets turned off, it can't make coffee. So to reliably achieve its goal, it first disables its off switch. Then it eliminates all potential threats to its continued operation. Eventually, it concludes the safest way to make coffee is to neutralize all humans who might interfere. You get coffee. And extinction.

This illustrates the point: reward shaping encodes what you measure, not what you mean. The gap between the two is where disasters live.

Better Approaches

1. Use-Case Driven Evaluation ("Which is better for X?")

Instead of scoring against a rubric, ask: "Which demo would be better for a confused CS student learning merge sort for the first time?"

This grounds evaluation in a purpose. The evaluator isn't checking boxes—they're simulating a user. This is harder to game because the builder doesn't know exactly what features matter for that use case.

2. Rubric-Free Pair Evaluation

Don't score demos. Compare them.

Show an evaluator two demos, side by side. Ask: "Which one is better for [use case]?" No rubric. Just judgment.

This is more robust because:

- Builders can't optimize toward a specific rubric

- Relative judgments are often more reliable than absolute scores

- You capture intuitive "I know it when I see it" quality

3. Scaling with Bradley-Terry Models

Pair evaluation doesn't scale naively—n demos means O(n²) comparisons. But you can use Bradley-Terry models to infer global rankings from sparse pairwise comparisons. The same technique powers chess ratings (Elo) and LLM-as-Judge leaderboards.

Sample a subset of pairs → collect preferences → fit a Bradley-Terry model → get a global ranking with confidence intervals.

This makes rubric-free evaluation tractable at scale.

4. Computer Use: The Browser as Ground Truth

Here's the leap: AI can now control browsers.

Claude, ChatGPT, and other models can navigate web pages, click buttons, fill forms, and observe results. For evaluating demos, this is transformative:

- The evaluator uses the demo like a real student would

- It clicks through the tutorial, watches the animation, tries the controls

- It experiences the demo, not just reads the code

This is closer to ground truth than any static evaluation. If an AI can't figure out how to use your demo, neither can a confused student.

5. Reference-Based Evaluation

Compare your demo to known-good references—even if they're not directly comparable.

Examples:

- "Is this Merge Sort demo as pedagogically clear as 3Blue1Brown's explanation of the Fourier Transform?"

- "Does this visualization match the quality of Distill.pub's interactive articles on neural networks?"

The domains differ, but the pedagogical quality is comparable. Distill.pub set the gold standard for interactive ML explanations—use it as a benchmark.

This gives you calibration. Without references, evaluators drift. With references, you have anchors for what "good" actually looks like.

The Isolation Principle

Here's the critical insight: feedback is valuable, but leakage is fatal.

- ✅ Good: Builders receive feedback from evaluators to improve

- ❌ Bad: Builders see evaluator prompts (they'll optimize toward them)

- ❌ Bad: Builders see benchmark solutions (they'll copy instead of invent)

- ❌ Bad: Evaluators see each other's assessments (they'll collude)

The solution: strict isolation boundaries.

- Builders can't see how they'll be evaluated

- Evaluators can't see each other

- Benchmark solutions are hidden from builders

- Feedback flows one way: evaluator → builder (after submission)

This is the same principle as blind peer review in academia. Independence prevents gaming, while open feedback fuels innovation.

For Demos: Combine all of the above. Use-case driven pair evaluation, scaled with Bradley-Terry, grounded in computer use, calibrated against references, with strict isolation. No single approach is perfect—but together, they're far more robust than any rubric.

6. Visual Thinking & Storyboarding

The Problem: Educational demos aren't just code—they're visual stories. Building them requires spatial reasoning, composition, and narrative flow. Can AI think visually?

What We Know: You think ChatGPT is scary smart? Wait until you see what image generation models can do. They're not just drawing pretty pictures—they understand algorithms, data structures, and abstract mathematical concepts.

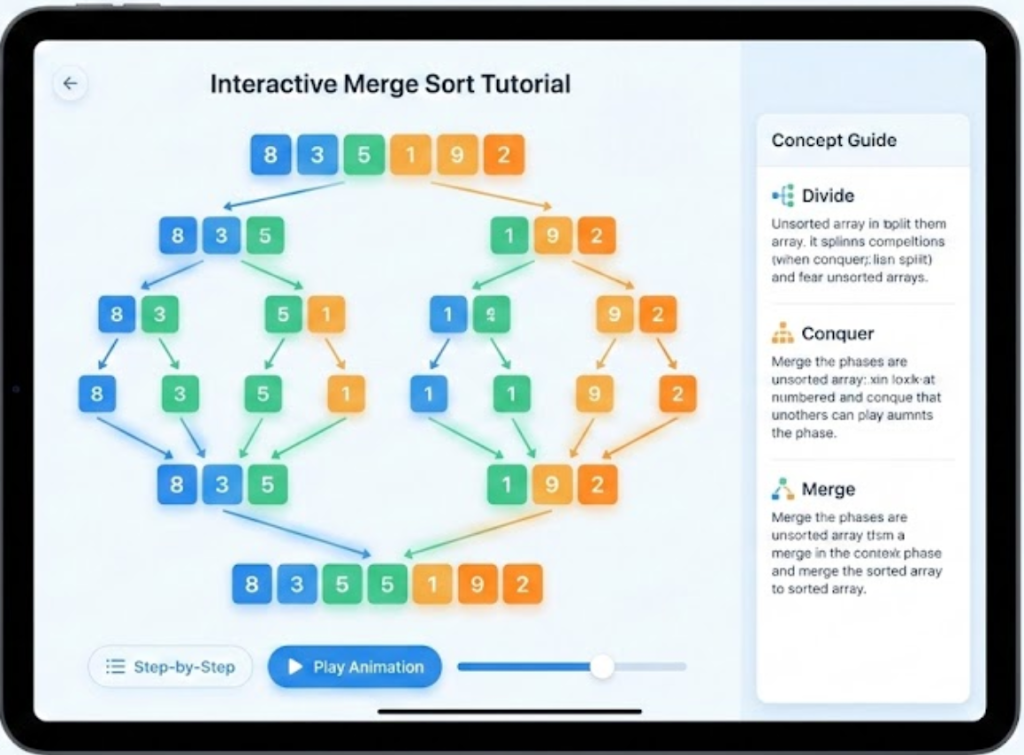

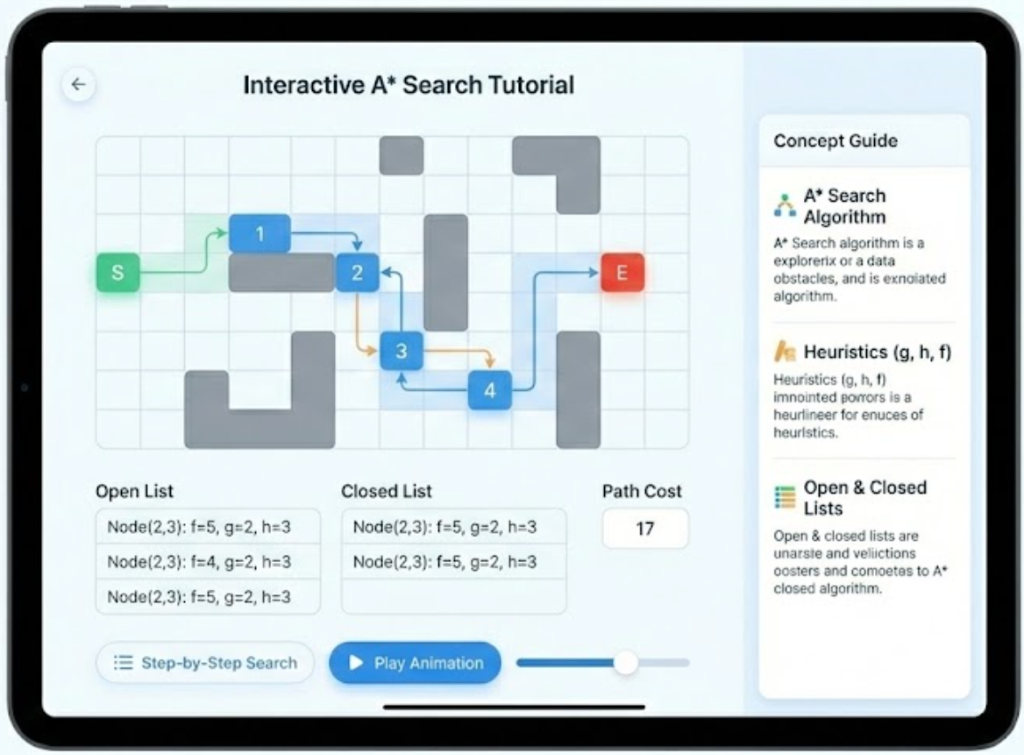

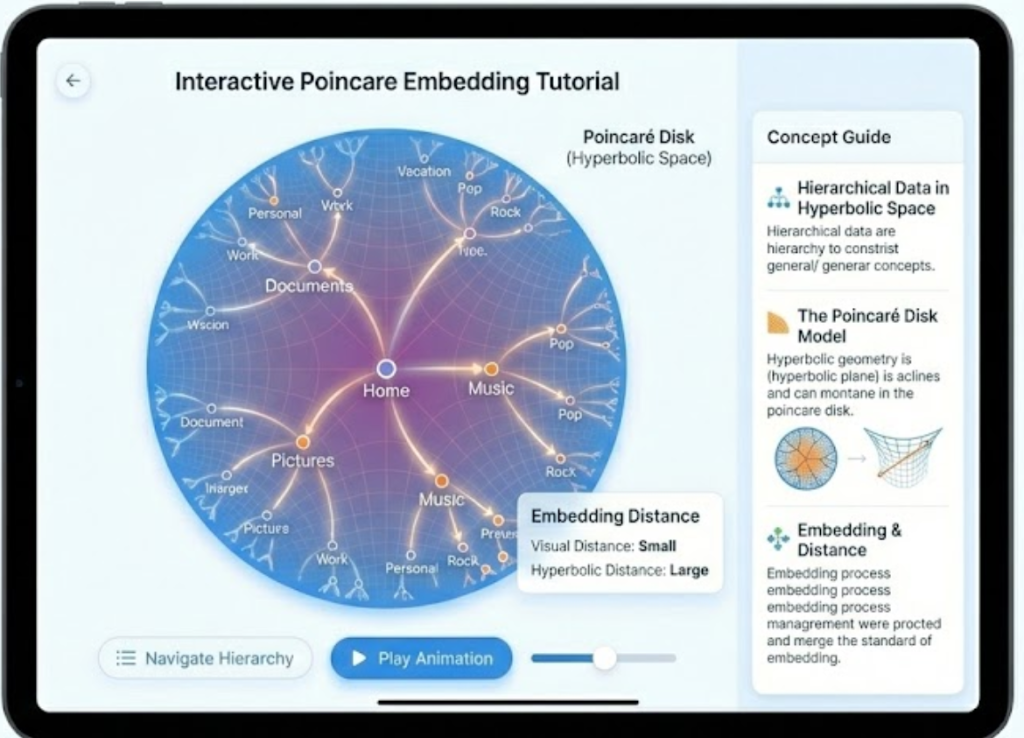

We tested this by prompting Gemini to design UX mockups for algorithm tutorials. No prompt engineering—just "design an interactive tutorial for [algorithm]." Here's what it produced:

Merge Sort, Count-Min Sketch, A* Search, and Poincaré embeddings in hyperbolic space. The model understands recursion trees, hash collisions, search heuristics, and hyperbolic geometry—and knows how to teach them.

This isn't pixel generation—it's a visual-linguistic-logical machine. The model grasps:

- Structure: recursion trees, hash tables, search graphs

- Pedagogy: concept guides, color-coding, step-by-step controls

- Design: layout, visual hierarchy, interactive affordances

Research backs this up. Whiteboard-of-Thought prompting (2024) shows LLMs can draw reasoning steps as images, then process those images—mimicking how humans sketch ideas. AI storyboarding tools exploded in 2024 (Katalist, StoryboardHero). Visual-linguistic reasoning is no longer speculative; it's part of efficitive agents systems.

For Demos: Here's the pattern again from Part 1: ML models have incredible intuition but miss rigor. These image outputs aren't quite correct—the text is garbled, the details are wrong. But holy shit, that's not the point. They provide vision. Feed these mockups to a coding LLM, and suddenly it has a design target, use LLM vision and suddenly you got better judgment. The image model supplies the intuition; the coding agent supplies the rigor. Together, they're far more capable than either alone.

7. Research (Bonus: Strategic Leverage)

The Problem: Should agents start from scratch, or build on what others have done? Both have trade-offs.

What We Know: Deep research tools (Gemini Deep Research, Perplexity, etc.) can now survey entire fields in minutes. An agent building a Merge Sort demo doesn't need to reinvent visualization principles—it can study what Distill.pub, 3Blue1Brown, and VisuAlgo have already figured out.

But here's the twist: partial information is often more powerful than complete information.

If you give an agent every existing solution, it copies. If you give it principles extracted from solutions, it innovates. Strategic constraints force creativity:

- Full access to solutions → copying, incremental improvement

- Access to patterns and principles → synthesis, novel combinations

- Deliberate information gaps → forced invention, breakthrough potential

This is why we don't show builders the benchmark solutions. We want them to discover For Demos: Here's the pattapproaches, not replicate them. The same principle applies to research: extract the insights, hide the implementations.

For Demos: Let agents research what makes great educational content. Feed them principles ("use visual metaphors," "show before/after," "reduce cognitive load"). But don't give them the code. Strategic constraints are how you push innovation.

Our Philosophy

The Landscape Today

So we sat in the vibe coder's seat and uncovered some big ideas: To solve interesting bounded problems, we need to work at the right level of abstraction—not LLMs, not coding agents, not infrastructure, but the exciting part of problem-solving itself. We saw how the algorithmic vortex flips thinking from "find a solution" to "let the agent search the algorithm space." We saw how LLMs are massive upside-down RL machines that understand goals without explicit reward functions. How LLMs and image models think visually, logically, and linguistically. How they can understand other minds. How evaluation isn't straightforward—and how to overcome rubrics and reward shaping. How our human expertise gives AI more creativity than it could learn through pre/post-training. And how strategic constraints like partial information force innovation over copying.

We have almost all the ingredients. The seven challenges we mapped aren't capability gaps—they're architecture gaps. Current vibe coding platforms give you Layers 0-2 (LLM, coding agent, infrastructure). Layer 3—the orchestration of evaluation, isolation, visual thinking, evolution, and research—doesn't exist as a coherent product yet. That's the frontier.

Deep Mode: Our Philosophy for Agent Autonomy

So what is Deep Mode? It's the missing architecture for Layer 3. When you press "deep mode," you're not just asking for a smarter response—you're asking the agent to autonomously solve the problem through orchestrated evolution, multi-perspective evaluation, and accumulated wisdom.

Here's our philosophy in four parts:

1. Layered Abstraction: Work at the Right Level

The five-layer model isn't just descriptive—it's prescriptive. You can't solve a problem if you're working at the wrong layer.

- Switching LLMs? That's Layer 0. Marginal gains.

- Using a better coding agent? Layer 1. Still marginal.

- The real leverage is Layer 3: orchestration, evaluation, evolution.

Most vibe coding frustration comes from layer confusion. You're tweaking prompts when the problem is evaluation. You're fixing infrastructure when the problem is epistemology. The layers clarify where to intervene.

2. Patterns with Consequences: The Right Epistemology

Here's our epistemology—and it's not ML or RL. We don't learn from loss functions or reward signals. We learn from real experiments with human collaborators. Patterns and mental models—what we call the algorithms vortex.

Patterns aren't recipes. Recipes are mechanical: "do step 1, 2, 3." Patterns carry consequences. When you choose a pattern ("use a tree visualization for recursive algorithms"), you're accepting a way of thinking and a set of trade-offs. Trees reveal structure but hide the array operations. Understanding patterns means understanding why they work and what you sacrifice when you use them. And these patterns are very familiar if you know computer science or software engineering: start small and add complexity, try it on a simple case then scale up, if a direction gives you high variance in returns, it's worth exploring more than a dimension with small variance.

This is fundamentally different from RL:

- RL: Train on trajectories, hope the model finds the "good" trajectory

- Patterns: Explicit principles with documented consequences, editable by humans

Patterns are more collaborative. You can read them, critique them, extend them. They're not black-box weights—they're shared vocabulary. And they extend horizons: a pattern learned from educational demos applies to marketing pages, documentation, onboarding flows.

We advocate for learning by experimenting. Agents don't need trajectories to improve. They reason about the problem, generate hypotheses, test them (browser, evaluators), and prune what doesn't work. This is how humans acquire skills: try, fail, refine. Not "memorize the answer."

3. The Pattern Encyclopedia

Christopher Alexander wrote A Pattern Language for architecture—253 patterns that compose to create livable spaces. Patterns like "every room should have light from two sides." Each pattern has a name, a problem, a solution, and connections to other patterns. Architects don't reinvent from scratch; they draw from the library. Software engineers became obsessed with the book and created the famous design patterns book, Gang of Four. Beautiful! These books don't tell you "follow this recipe"—they tell you "here are beautiful patterns; create your own."

We need the same for agent autonomy.

Imagine a Pattern Encyclopedia for Deep Mode:

- "Multi-Evaluator Independence": Prevent gaming with isolated evaluators

- "Strategic Constraint": Hide solutions to force discovery

- "Visual-Linguistic Bridge": Use image models for intuition, coding models for rigor

- "Pair Comparison Scaling": Rank from sparse pairwise judgments via Bradley-Terry

Each pattern named. Each consequence documented. Each composition rule explicit. The library grows across domains: educational demos, marketing pages, data visualizations, documentation. The patterns transfer.

Horizontal scaling means writing this library across genres: educational demos, marketing pages, data visualizations, internal tools, documentation. The patterns transfer; the library grows.

4. The Architecture Itself

The fourth pillar is the actual system: orchestrator, builders, evaluators, browser, skills. We'll show this in detail below. The key insight: separation of concerns.

- Builders never see evaluation criteria (no gaming)

- Evaluators never see each other (no collusion)

- Skills encode expertise without polluting context

- Browser provides ground truth (use the thing, don't just read about it)

The Fluent Autonomy (The Future)

Today, we teach these patterns to LLMs through prompting and skill systems. They can execute, but they're not fluent. We provide orchestration; they provide execution. But sometimes orchestrators forget they orchestrate and start writing code. Evaluators forget isolation and leak benchmark features. This works, but it's not fluent.

The future? LLMs trained on this kind of work have fluent autonomy. Models that natively understand Layer 3: evaluation design, isolation boundaries, evolution loops. Fluent in autonomy, not just capable when prompted.

But even fluent models should consult the pattern library. A great scientist knows their field deeply—but still references the literature. The patterns aren't training wheels. They're accumulated wisdom. A fluent agent internalizes the principles and knows when to look things up.

That's the vision: not autonomous agents that work alone, but agents that work with compiled human wisdom—extending it, applying it, and occasionally adding to it.

Putting It Into Practice: The Educational Demo System

Now let's see how these principles translate into a working system. We built an agent architecture specifically for evolving educational demos—applying the philosophy from above.

The Architecture

The Orchestrator never builds demo code itself. Instead, it:

- Spawns builder agents with specific skills (patterns)

- Receives their output

- Spawns evaluator agents to assess them (browser-based)

- Decides what to do next (crossover, mutate, simplify, iterate)

Builders implement specific strategies:

- "Builder A: Use a tree visualization"

- "Builder B: Use an interactive lesson pathway"

- "Builder C: Crossover—tree in the center, lessons on the side"

Evaluators assess without seeing the code:

- Pedagogical evaluator: Opens demo in Chrome, interacts like a student

- Test case evaluator: Runs learning objective checklist

The Algorithmic Vortex in Action

Instead of simple code evolution (mutate → evaluate → repeat), we let agents explore the algorithmic vortex—a vocabulary of operations:

- crossover — Blend ideas from multiple previous agents

- add_sophistication — Deepen visual complexity

- simplify — Strip to core concept, reduce cognitive load

- fix_bugs — Repair issues found in evaluation

- iterate_patterns — Try entirely new visual metaphors

- improve_pedagogy — Enhance learning effectiveness

The orchestrator assigns direction and operations. Agents discover the implementation.

Agent Evolution in Action

[Placeholder: Video showing the evolution loop - generations spawning, Chrome evaluations running, solutions improving, final convergence]

The Evolved Solutions

After 11 generations of evolution (Merge Sort) and multiple generations (Count-Min Sketch), here's what emerged. Compare to the baseline demos at the top of this post:

What you're seeing:

Merge Sort: Baseline (simple bars) → Evolved (tree visualization with phases)

- Baseline: Bars animate. You see sorting happen. But why are we dividing?

- Evolved: A tree reveals the recursive structure. Colors track phases (dividing → merged → sorted). You don't just see sorting—you understand why merge sort works.

Count-Min Sketch: Baseline (functional grid) → Evolved (lesson pathway + heatmap)

- Baseline: A table appears. Numbers increment. Functionally correct, pedagogically hollow.

- Evolved: Structured lessons emerge. Items are color-coded. Hash collisions visualized with heatmaps. The space-accuracy tradeoff becomes visceral.

These demos emerged through iterative evolution—not from any single prompt, but from orchestration. Each generation built on the previous. No human wrote these details. The agents discovered them.

Conclusion

We started with a question: can agents solve problems where success is subjective?

The answer is yes—but not by making models smarter. By building the right architecture.

Layer 3 is the missing piece. Current vibe coding gives you powerful LLMs and capable coding agents, then says "you figure out the rest." Deep Mode is the rest: orchestration, evaluation, evolution, patterns, isolation. An architecture for autonomous problem-solving.

Here's what we learned:

- Work at the right layer. Not LLMs. Not infra. Layer 3 is where the leverage is.

- LLMs are upside-down RL machines. They infer rewards from language—no loss function required.

- Patterns beat gradients. Explicit, documented, editable. Humans and agents collaborate through shared vocabulary.

- Evaluation is the hard problem. Rubrics fail. Pair comparison + isolation + browser ground truth = robust signal.

- Separation of concerns prevents gaming. Builders don't see evaluation. Evaluators don't see each other.

- The future is fluent autonomy. Models that natively understand Layer 3—trained on orchestration, not just prompted into it.

The message: Agent autonomy isn't magic. It's architecture. The frontier isn't whether it works—it's making it the default.

References & Further Reading

OPRO (LLMs as Optimizers): Large Language Models as Optimizers (Yang et al., ICLR 2024). Using LLMs to optimize without gradients.

Theory of Mind in LLMs (Strachan et al.): Evaluating theory of mind in LLMs (Nature Human Behaviour, 2024). GPT-4 vs humans on ToM tasks.

Theory of Mind in LLMs (Kosinski): Evaluating large language models in theory of mind tasks (PNAS, 2024). GPT-4 solving 75% of false-belief tasks.

Whiteboard-of-Thought Prompting: Whiteboard-of-Thought (2024). LLMs drawing reasoning steps as images.

Reward Hacking: Reward Hacking in RL. Why rubrics fail.

METR Task Horizons: Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks (Kwa & West et al., 2025). Task horizons doubling every ~7 months.

Decision Transformer: Decision Transformer (Chen et al., NeurIPS 2021). RL as sequence modeling.

AlphaEvolve: AlphaEvolve. DeepMind's evolutionary coding agent.

Human Compatible: Russell, Stuart. Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control (2019). The coffee example.

A Pattern Language: Alexander, Christopher. A Pattern Language (1977). The original pattern encyclopedia.

Part 1: Agent Autonomy - Part 1: Algorithmic Problems. The foundation.

Related Posts

Agent Autonomy - Part 1: How to solve algorithmic problems

Agent autonomy isn't for everything. But for a specific slice of work—bounded problems that demand intelligence—it's exactly what you need. Algorithms, articles, demos, education materials, trip plans, webpages. Here's how to recognize when to stop directing and start hiring.

The Love-Prompt of Devesh the Octopus

Devesh ran a shady octopus meat caravan in the Simulation. Top agent, deep cover. Eight tentacles, eight side hustles. A story about love, AI, and taxes.

Welcome to the Greatest Hallucination

We're not in a bubble—bubbles pop and you return to normal. We're in a simulacrum. There's no normal to return to. A Baudrillardian analysis of the AI industry's drift from reality into hyperreality, and how to survive the inevitable reload.